The Keynesian Beauty Contest

"My business is to paint what I see, not what I know is there." — J. M. W. Turner

A men’s magazine has a competition where you have to guess which Miss Universe contestant will receive the most votes from all the readers of the magazine. The readers who select the Miss Universe contestant with the most votes are entered into a draw to win a prize. It's important to note that it doesn't matter which Miss Universe contestant eventually wins the entire pageant. You believe that Miss Greece is the most beautiful contestant; there’s just something in her smile that makes the story of Helen of Troy having the face that launched a thousand ships plausible. However, selecting Miss Greece i.e. choosing a contestant based on your own conception of beauty would be to follow a naive strategy.

A smarter approach would be to guess the majority's perception of attractiveness and then select that contestant as your own choice. Let’s assume that Miss Sweden’s hair and eyes are trance-inducing to the average male and it is likely that many readers will pick her in an uncomplicated ‘I see hot blonde, I like’ manner.

Miss Sweden gets the largest number of votes, so all the readers who picked her are entered into the draw. You could take this further and assume that other readers are also employing this strategy and forecast what others will guess as their fellow readers’ choices.

Thus, this strategy can be applied recursively to the nth order and with readers at each level predicting the top-voted contestant based on the reasoning of other rational agents. Game theorists will recognize this convergence as the focal point or Schelling point. To qualify for the draw, you must select Miss Sweden even if you find Miss Greece the most beautiful because that is how the incentives are structured.

"It is not a case of choosing those that, to the best of one's judgment, are really the prettiest, nor even those that average opinion genuinely thinks the prettiest. We have reached the third degree where we devote our intelligences to anticipating what average opinion expects the average opinion to be. And there are some, I believe, who practice the fourth, fifth and higher degrees." — John Maynard Keynes

Keynes believed, and I concur, that a similar dynamic is at work in financial markets: investors' pricing of an asset is based on their own analysis of the asset's fundamental value1 and on what they believe is other investors' assessment of the asset price. Each investor downplays/ignores fundamental value, and instead tries to predict what other investors will do.There isn't an apt term for this type of investing where an investor updates their assessment of price based on their forecast of other investors' valuation as well as fundamental analysis in order to get closer to a "final" price so I'm taking the liberty to call this Recursive Investing2.

Reflexivity, a theory advocated by George Soros, is a related but different concept that refers to a positive feedback loop of rising/falling prices leading to higher/lower prices.

Sidenote 1: What’s the difference between investing and speculating?

I’ll attempt to distinguish investors from speculators here: investors buy/sell assets when they see a disequilibrium between the asset’s price and its value based on the assets’ economics; while speculators are focused on market psychology i.e. the behavior of other market participants. It’s a spectrum rather than a dichotomy and most investors fall somewhere in between the extremes.

These definitions seem fuzzy because dealing with the semantics is tough and even the greats, Benjamin Graham, David Dodd, or John Maynard Keynes could not produce completely satisfactory definitions. Even so, all of them focused on the way a market participant aimed to realize a profit rather than the investor's motive, time-horizon, or asset class. Keynes noted that the lines between investing and speculation were blurred in 1936.

Value investors try to buy stocks that are cheap, and growth investors try to buy stocks that will grow quickly. While no investor wants to buy stocks that are expensive or stocks of companies that will shrink, what both sets of investors are really doing is trying to buy stocks that will go up in value — stocks that they think other investors will decide should be worth more.

The interaction between perceived valuation and price is probably stronger in private markets. According to Peter Thiel, generating returns in venture capital necessitates making investments that are initially seen as crazy/contrarian but will eventually become the consensus. If something is seen as crazy or uninteresting, not many will want to invest in it which allows you to invest at a favorable price.

The value of a venture capitalist's stake only increases when the startup receives an investment from another VC fund at a higher valuation and the stake is marked up or the startup goes public and the public markets think it is a good investment and bid up the stock price. It is remarkable that venture capitalists conventionally, and almost exclusively, use the word valuation because it makes it sound like the price they paid is grounded in actual business performance and other fundamental analysis, but venture capitalists are actually recursive investing3 .

Time Horizon

"Our investments are simply not aware that it takes 365 ¼ days for the Earth to make it around the Sun." — Warren Buffett

Buying an asset today that the market does not care for is fine as long as the rest of the market eventually comes around to accepting your point of view sooner rather than later. To beat the market, an investment manager has to have a 'view', or an investment thesis on 'why' and 'how' other investors will change their minds. This view can but doesn't require a 'catalyst' i.e. an event 'when' other investors will change their mind.For venture capital, a catalyst is analogous to startups riding 'a wave' of market creation & expansion such as the gig economy, change in banking/healthcare legislation, devsumer (a portmanteau of 'developer' & 'consumer'), remote work, or some other secular trend that creates an opportunity for a startup to grow its revenue rapidly.

Investment managers can accelerate the convergence of their point of view and the perceptions of others by releasing white papers that lay out their investment theses (Andrew Left of Citron Research and other short-sellers are examples). A subtler and more common way of doing this is by convincing other managers and sell-side researchers of their investment thesis.

For example, assume it’s July, you're a portfolio manager at Smart Money Fund. You determine that Chipotle stock is undervalued from your discussions with industry experts and your analysis of the company's financials. However, you have gleaned the market sentiment by chatting with sell-side analysts and you think that other investors assess Domino's Pizza to be a much better bet for the next 9-12 months. This means you can’t buy Chipotle because the other investors won’t come around to the same conclusion as you in time to bid up the value of your Chipotle investment before your performance evaluation period ends on 31st December.

To understand how organizational behavior affects investment decisions it would help to understand the org chart of the investment team. A large fund's assets are split into sub-funds by asset class, geography, sector, etc. and a portfolio manager manages each sub-fund. The Chief Investment Officer manages all portfolio managers.

Portfolio managers' performance evaluation period is January to December each year (in addition to rolling 3- and 5- year periods). This evaluation determines their compensation so a portfolio manager must look at assets that will provide the best return within the time frame of their next performance evaluation. Certain global macro hedge funds and other funds which trade liquid assets even crystallize (or earn) their carry fees quarterly, making their evaluation period just 3 months.

Some funds have a Darwinian philosophy4 where sub-funds that generated strong returns in a single evaluation period get more assets allocated to them in the subsequent period, while weaker teams get fewer assets or even get sacked depending on the severity of underperformance5. Internal competition, coupled with firms’ organizational behavior and other HR bureaucracy-related systems such as corporate politics involving quarterly, semi-annual, & annual reviews, promotion cycles, etc. incentivize portfolio managers and investment analysts to game the system for short-term gains and job security.

Thus, investment managers attain the local maxima (a decent return in each period), and not the global optimum (an asset that underperforms in the short-term but will generate strong returns only after employer or LP review is complete).

The long-term is a series of short-terms in the investment management industry.

Sidenote 2: Time Arbitrage

Warren Buffet (and other value investors) have a competitive advantage because his time horizon is much longer so he has leeway to select investments that will eventually outperform so he earns a premium from his time arbitrage. His track record makes him immune to the short-term pressures that other CIOs and investment managers face from their own LPs6.

Social Psychology

"It is always easiest to run with the herd; at times, it can take a deep reservoir of courage and conviction to stand apart from it. Yet distancing yourself from the crowd is an essential component of long-term investment success." — Seth Klarman

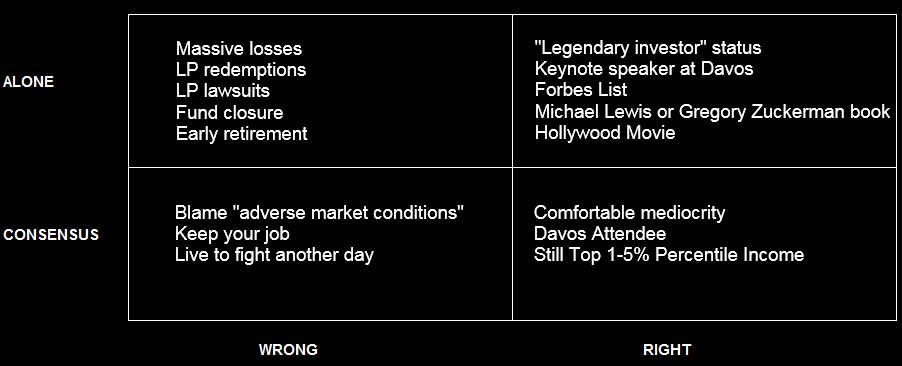

Social pressure is the third factor uncoupling assets' values and prices because it forces investors to focus on the consensus opinion rather than use their independent judgment to value assets. Your analysis can be right or wrong, and it can be with the consensus or contrarian. ‘Contrarian’ has connotations of being a Thoreau-like frontiersman or having a Galileo-like commitment to the truth, but considering the social dynamics I’ll soon detail, a better word would probably be 'alone’.

When you’re right and the consensus is also correct, your LPs get the average return or a substantially worse return than an index fund after factoring in the investment management fees7.

When you’re wrong and your peers are also wrong, the underperformance is chalked up to the “irrational exuberance” or “a market correction”.

There is the special stigma of being wrong and alone and this is when things get really dicey. Depending on the magnitude of the error, it is likely that LPs will question your judgment, your investment process, your risk management processes, the way you run your firm, and may even ask to redeem their capital. Financial journalists, who once called you “visionary”, “maverick”, and “genius” when they put you on the covers of their magazines on your way up, will now call you "an arrogant, reckless has-been whose best days are behind him".

Investment funds are ranked according to decile or quartile so your marketing team's pitch and investor relations team's reports to investors will also be much weaker when they show that your fund is not in the top deciles/quartiles. Unless things change quickly, your fund gets trapped in a downward spiral towards poor performance, employee turnover, asset redemptions (LPs withdraw their funds), fund closure, and finally, your early retirement.

If you’ve decided not to follow the herd when the market is going up, the FOMO is also just as strong, if not even stronger. The large funds are completely captured by this sentiment because over time, most of their income comes from management fees, and hence, investment managers' primary motivation & incentive is to hold on to their assets under management with mediocre performance for long enough to become wealthy. In other words, don't rock the boat and just be competent enough to not get fired by your LPs and you're on your way to a decent fortune.

You want to be only slightly ahead of the herd and not venture too far out, else you'll end up isolated if the herd doesn't follow after you so it is a lot safer to be somewhere in the middle of the herd.

To recap, the three factors that prevent investment managers from expressing their real opinion on the market are (1) the game-theoretical nature of the industry, (2) the mechanics of performance measurement & organizational behavior of investment funds, and (3) the powerful effects of social psychology8 (obviously, this is only a partial list and there are several reasons why asset prices and their intrinsic valuations diverge).

Don’t hate the player; hate the game.

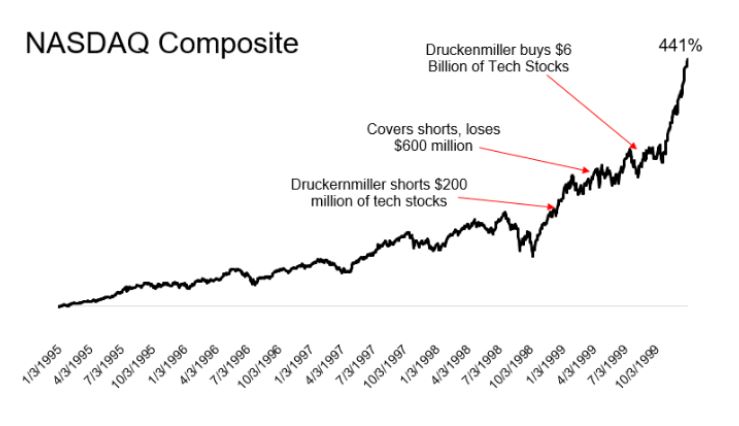

Case Study: Dotcom Druckenmiller Was "Right"

In early 1999, Druckenmiller shorted $200 million worth of tech stocks when he was the CIO of George Soros’s Quantum Fund. He ignored other investors who were buying as much dotcom stock as they could and he put on his short trade too early: the Dotcom Boom forced him to cover his short a few months later, and after racking up a $600 million loss. Through May 1999, the fund was down 18% while the NASDAQ Composite was up 15% and the S&P 500 was up 10% which means he was underperforming by 33% (-18-15) or 28% (-18-10) depending on the benchmark he was supposed to beat.He was too far from the herd and couldn't stand the prolonged pressure of being temporarily "wrong" and alone. Had he persisted, he eventually would have had his own 'The Big Short' trade when the bubble burst in March 2000. Too early is the same as being wrong in public markets and that’s the crux of the aphorism “the market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent”. If the market is irrational and is pulling you away from the rational choice, you are better off surfing the wave while holding on for dear life rather than trying to be a stick in a storm.

Source: The Irrelevant Investor

Footnotes

- For a definition of fundamental value, feel free to take your pick: the present value of total expected cash flow; expected profitability based on expected revenues and costs; or whichever you prefer as long as it primarily considers the fundamentals and economics of the asset. Some believe an asset's price is whatever someone is willing to pay for it, and the entire value-price debate and the idea of intrinsic value are both irrelevant.

- Recursion refers to a function that invokes itself, and is thus, repetitive and self-referential until it reaches its "base" condition (from Latin recursiō, “the act of running back" or "again, return”).

- Alex Danco first noted this clever semantic trick.

- Herbert Spencer first used the phrase "survival of the fittest" after reading Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species.

- The Matthew Effect of Accumulated Advantage is applicable to matters of fame, status, and the cumulative advantage of economic capital. "For to every one who has will more be given, and he will have abundance; but from him who has not, even what he has will be taken away." — Matthew 25:29.

- Flashes of 'Counter Positioning' (7 Powers by Hamilton Helmer) can be detected: Buffet's business model cannot be copied by competitors because it will damage their existing business. It's not a perfect instance of Counter Positioning because the evolution of the industry was very different compared to the textbook cases.

- Funds that are very similar to the broad index are pejoratively called ‘closet indexers’ or ‘index huggers’. Closet indexing is suboptimal for investors because investors are charged much higher fees (100-200 basis points or 1-2%) for “active” management plus incentive fees (1,400-2,000 basis points or 14-20%) compared to a passively managed fund i.e. an index fund, which simply tracks the market for 9-25 basis points (0.09-0.25%) in fees.

- Collectively, I'd contend that these three factors are also arguments against market efficiency.